Advent of Code Golf

Every year, I play Advent of Code, an advent calendar of coding puzzles by Eric Wastl. Last year I solved all the 25 challenges, and this year I planned too, but I wanted an extra challenge. I decided to spend hours writing horrible, unreadable, bodged-together code full of code smells, bad practices, and hacks.

I decided to do Code Golf.

A Code Golf, as Wikipedia beautifully names it, is a “recreational programming” challenge to write the smallest program that solves the task. Like in golf, you compete to complete the assignment in the smallest number of (key)strokes, hence the name.

![n-=1;P={i,j}\nfor k,c in[*E(C)][::-1]:P|=c&P and C.pop(k)\nC.append(P)\nfor c in S(map(F,C*(n==0)))[-3:]:V*=c](/articles/advent-of-code-golf-2025/example.png)

Here is how it went:

Rules (sort of)

Code Golf is not a real sport, so it doesn’t have a standardized set of rules. I give the following guidelines to myself:

- Write only python code, standard library allowed

- “Common enough*” packages are allowed too

- Achieve the shortest program possible

- Little-known coding tricks and CPython-specific hacks and

eval()are allowed - Using knowledge you gain from analyzing the data retroactively to make shortcuts is NOT allowed**

- Input data are presumed to pre-exist in a single-letter-named string variable. Neither the input data itself, nor loading the data from disk or stdio counts towards the number of characters (but any processing of the data of course does)***

A few asterisks to address:

*: First, it is hard to precisely define “common enough” packages, and I decide arbitrarily on what’s allowed. For AoC, I mostly mean numpy, scipy, pandas, and other scientific tools. I am allowing these because, most of the time, two lines from libraryname import* and needed_func(v1,v2,v3) are surprisingly toooooo long, and implementation from scratch ends up being shorter (with the exception of day 10 part 2 puzzle, where the whole solution is a single call to linprog from scipy.optimize).

**: Then, for the guideline 5, the point is that the code must solve the general case of the problem presented for any valid data, not only for the specific input data from AoC website. It is totally ok to use a shortcut if the code still works correctly. It is ok as well to prove some theorem about the equivalence of the problem to a simpler problem. It is NOT ok to look into the data and skip some cases (I violated this rule on the last day).

For example, in day 11 part 2, you need to add up 2 paths, but you can prove that for valid input data, only one of them can be non-zero, and the other must be zero. Following this guiding principle, it would be ok to exit early if the code found that the first path was the non-zero one. But if I myself look at the results, see which path is non-zero, and skip coding the other path, then this is not ok. If I am allowed to pre-calculate something, I could just as well pre-run the whole code, find the answers, and write print("solution1","solution2") for my Code Golf solution, which obviously wouldn’t fit the spirit:

***: The rule 6 exists because I tried to participate in an online competition, but different platforms have different expectations. Golfcoder’s implementation expects me to read data from stdin and print. If I were to play Code Golf on Leetcode, I would need to make a function taking data as a variable and returning the result. I don’t want these discrepancies to come in the way of me golfing. Thus, since loading/returning data is standardized per platform, I optimized the load/return code once and then skipped any d=open(0).read() boilerplate code while counting symbols.

My solution flow

Here is my approach to solving “Advent of Code Golf”

- Solve the puzzle somehow,

- Think about alternative solutions algorithms,

- Choose one algorithm that I believe has the potential to be the shortest,

- Implement this algorithm clearly at the cost of many symbols,

- Then, do standard Code Golf tricks,

- Then, do semi-standard tricks,

- Then, do dark magic.

I kept each implementation in the same file, and copy-pasted the code before each attempt. This has two purposes. First, it made it easy for me to track how my thoughts have evolved at once without any extra tooling. It also helped me avoid a situation where I start working on 3 ideas at once, and in the end, get broken code that I have no clue how to fix.

I also used asserts for each copy of the code, to ensure that my shenanigans don’t break the solution 😅

The tricks that worked

The algorithm is the key. Let’s say you are given a puzzle that has 20 x N elves, and you need to count how many ways there are to arrange a seating at the table with 20 elves from this list. You could be iterating list until you get the answer. Or, you may recognize the “n choose k” formula, and just calculate 3 factorials. The latter will be shorter, no matter how much you try to optimize the former. Checking how much you can shorten any given algorithm takes a lot of time, so a good initial guess for the algorithm is very important. Also, remember that in Code Golf, the performance is NOT important. You have a fast O(logN) algorithm that solves the puzzle in 200 symbols? Thank you, but in Code Golf, if my input size allows, I’ll solve it in O(N^2) using 50 symbols instead.

Once settled on the algorithm, there are many tricks to use, too many. I will recommend these two posts: one, two that helped me start with Code Golf. Once you grasp their concepts, I highly recommend this glorious post full of wild ideas you haven’t thought about. And this post will give you more wild ideas. For me, there are three types of tricks: the good, the bad, and the ugly.

The good are the tricks that (subjectively) seem normal to me. For example, it is easy to understand that removing spaces to replace a == 3 with a==3 saves space and changes virtually nothing. The same way, using 11-symbol implicit boolean testing if i+j:N+=1 instead of more wordy 14-symbol if i+j!=0:N+=1 seems obvious.

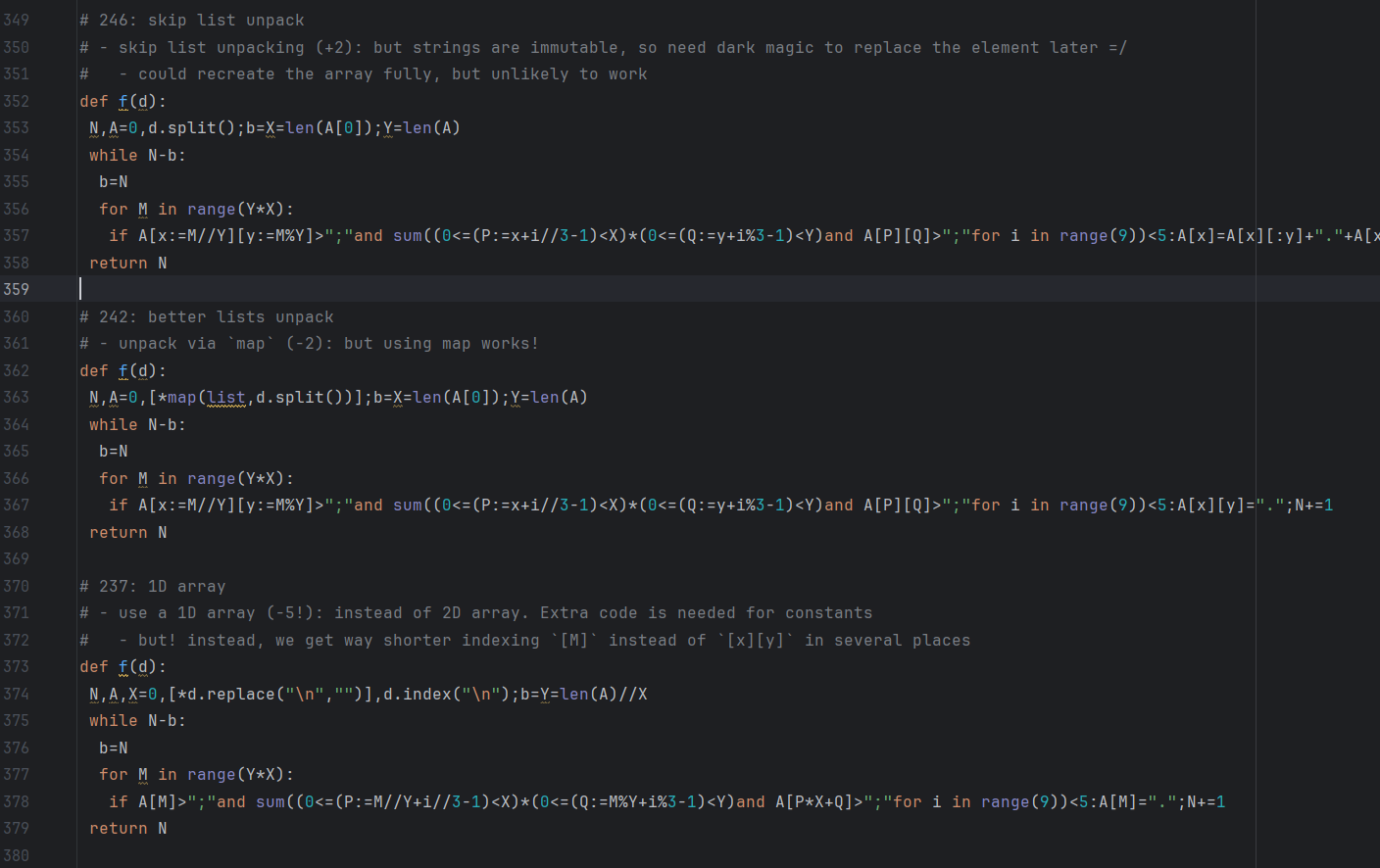

The bad are the tricks that use implicit conventions and unclear features that you do not want in your production code, but that save you symbols. 11-symbol if i+j:N+=1 is good, but how about N+=i+j!=0 that saves two more symbols and also skips if that might save an indent while inlining? Speaking on inlining, this is almost always a good “bad” idea - but beware that it makes code lines long very quickly:

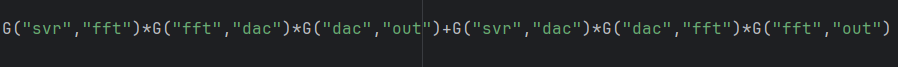

The ugly are the tricks that do change logic, but for the particular puzzle and algorithm, they do not break the solution and allow magic like the code from the top of the post:

P={i,j}

for k,c in[*E(C)]:P|=P&c and C.pop(k)

C.append(P)

Two bad tricks are used here. First, with .pop we are consuming an iterable as we iterate over it in E(C) (which is an enumerate() call, so that is ok). Then, we use lazy evaluation by and, meaning the .pop doesn’t trigger if P&c is an empty set.

But there is also an ugly trick. For it, you need to know that we shouldn’t be testing P&c, but {i,j}&c in the second line. However, we can prove (I won’t go into details here) that for this particular task, and for this particular way we constructed C and P, the set P&c is identical to the set {i,j}&c, so we can replace one with the another. This is not an identical replacement in general, but it is identical for our case.

Results

In some puzzles, part 1 and 2 were similar, so I solved both parts with the same code and golfed that code. In almost all other (barred day 6), I code golfed part 2.

All tricks combined, here are my stats for the length of my shortest solutions in python in characters for this year’s AoC:

| Day | Part 1 | Part 2 | Both |

|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | - | 109 | - |

| 02 | - | 148 | - |

| 03 | 80 | 113 | - |

| 04 | - | 209 | - |

| 05 | - | - | 256 |

| 06 | 115 | - | - |

| 07 | - | 129 | - |

| 08 | - | - | 346 |

| 09 | - | -* | - |

| 10 | - | 222 | - |

| 11 | - | - | 206 |

| 12 | 91** | 0** | 91** |

*: The 2nd part was the hardest puzzles the whole challenge in my opinion. I wasted so much time on it that I skipped doing Code Golf this day. This allows me to show how tiny the rest of these number are: my full solution for day 9 part 2 takes four functions and more than 3700 symbols. This is more than all the rest of the code golfed puzzles combined.

**: This puzzle only have one part, hence 0 for part 2; also my solution this day is filthy, and I struggle to claim that my result was honest 91 symbols.

In total, I found out that I solved at least one part of most of the AoC 2025 puzzles in just 2024 symbols. I think that is a magical coincidence for the year 2025 🎄 So I keep it at this. And I will definitely try to do next year 2026 in less than 2026 symbols too.