Advent of Code Golf, part 2

This year, I played “Advent of Code Golf”: a Code Golf over Advent of Code advent calendar of coding puzzles by Eric Wastl. In part 1, I described the self-imposed rules and my immediate results.

![n-=1;P={i,j}\nfor k,c in[*E(C)][::-1]:P|=c&P and C.pop(k)\nC.append(P)\nfor c in S(map(F,C*(n==0)))[-3:]:V*=c](/articles/advent-of-code-golf-2025-2/example.png)

Miraculously, I have managed to fit all my solutions in 2024 symbols (a perfect number for the 2025 calendar!). But as soon as I had written part 1, I became nagged by my results table. “All solutions” weren’t really all solutions. 5 out of 12 times, I Code Golfed only part 2. One time, I Golfed only part one. And one puzzle was missing entirely! That was worth improving.

Updated results

In many cases, part 1 was significantly shorter than part 2. But in even more cases, a solution for both parts at once was much shorter than two individual solutions together. I decided to Code Golf a solution to both parts at once.

Here are my results for solving the entire AoC 2025:1

| Day | Characters needed |

|---|---|

| 01 | 121 |

| 02 | 170 |

| 03 | 137 |

| 04 | 243 |

| 05 | 250 |

| 06 | 207 |

| 07 | 160 |

| 08 | 345 |

| 09 | 610 |

| 10 | 416 |

| 11 | 206 |

| 12 | 300 * |

| Total | 3165 |

*: for day 12, I still cheated a tiny bit, see “P.S.” at the end.

Grand unification

This result opens a new jar of worms. I really wanted to get down to 2025 characters. It was now out of question, so I was left unsatisfied. How could I have pushed the limit further? I knew that with 12 scripts, it was guaranteed I had some patterns, functions, imports, etc. that I could have reused and optimized if all 12 scripts were in the same file. At the very least, I used the print function to report results 12 times. So I knew that by unifying solutions to all 12 puzzles into one file, I could spare some characters.

For the first iteration, I just merged all the 12 input data strings, all 12 scripts, and all 23 tests into one file. I then immediately assigned the print function to a single-letter variable P. This wastes 8 characters, and thus, I didn’t need it for single-day solutions, where I only printed the result once. But for 12 scripts merged, I can now call P(text) instead of print(text), saving 4 characters per invocation, or 12*4-8=40 characters in total. This (and a few small tricks on top2) brought me down to 3117 characters.

P=print # uses 7 extra characters + 1 extra newline

...

P(output) # saves 4 characters in place of `print(output)`

Iteration 2: Repeated functions

It was good progress for almost no effort, but I couldn’t stop by replacing only the print function. There were more repeated functions in my code, here are the statistics:

| Function | Usages in all 12 solutions |

|---|---|

str.split | 17 |

range | 9 |

len | 8 |

int | 7 |

sum | 6 |

max | 6 |

eval | 4 |

abs | 4 |

sorted | 3 |

For the second iteration, I replaced these functions with single-letter variables. On top of that, I removed one repeating import statement. All together, this brought me down to 3003 characters.

Iteration 3: Repeated constants

The “3000” barrier became tantalizingly close. I decided to check if there were constants or variables that I kept reusing - and I found two cases.

First, I used -1 as a constant a lot. I could replace it with a variable, too, which would save one character per invocation. Luckily, I had twelve cases where -1 could be a variable. These cases included using -1 as an argument to range(a,b,-1), as a number in [::-1] slicing to invert lists, and as an index in [-1] to access the last item of lists.3

Second, I needed ten 0-initialized variables (counters, summators, etc.) for different tasks. There is a trick in python Code Golf to define several identical variables. Instead of defining them one-by-one, you may chain the assignments using v1=v2=v3=...=vn=0, saving 2 characters per each assignment after the first one:

# This needs 8 characters, and uses 4 characters per each next added variable

a=0 # 3 characters + 1 newline

b=0 # 3 characters + 1 newline

# This needs only 6 characters, and uses only 2 characters per each next added variable

a=b=0 # 5 characters + 1 newline

Combining these two tricks, I quickly brought the size down to 2988 characters.

Final Iteration: Polishing individual tasks

A few days later, I have done another revision. Most of the tricks were not about repetition, but improvements in individual tasks. I managed to squeeze another 50, bringing the number of characters down to 2938. I used only simple tricks that could save only a few characters per task.

By this time, I reached the diminishing returns: investing more time didn’t deliver significant savings anymore. I had no intention to review each task. I knew personally that my solution for Day 09 task was poorly made, programmed worse than all other tasks combined, and I never properly cleared it during Code Golf. So, as a final effort, I reworked Day 09, bringing down the solution length by about 20%, from 610 to 487 characters in the individual file. From the table above, I also knew that Day 10 was the second longest, but it was quite well-made. I quickly took a look and shaved off another 23 characters, from 416 to 393 characters. Bringing these new solutions to my unified file, I managed to shrink it down to 2784 characters.

In total, by unifying the solutions, I saved 177 symbols, and then another 204 by reviewing individual tasks, 381 in total:4

| Solution | Characters to solve both parts | Average per task |

|---|---|---|

| Start -> All days separately | 3165 | 263.75 |

Unified all days together & unified print | 3117 (-48 characters) | 259.75 |

| Unified other repeated functions | 3003 (-162) | 250.25 |

Shortened repeated -1 and 0-initialized vars | 2988 (-177) | 249.00 |

| Another look at all tasks | 2938 (-227) | 244.83 |

| Days 09 and 10 reworked -> Final version | 2784 (-381) | 232.00 |

The value of rewrites

Fiction authors rewrite their books several times all over before finally publishing them. The value of the rewrites is in the “purification” of the idea. As the book is being re-read and rewritten, the author purifies the main purpose of the written piece.

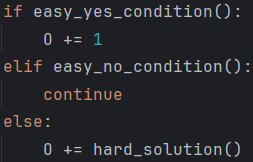

I saw a blog once that the same situation is true for programming. Take an average mature GitHub project, and you will see that over the span of life, it too gets rewritten several times. Take CPython repo, for example:

If you add up lines added and deleted with each individual commit, you will see that 12,915,596 lines of code were added, but 9,235,977 of those lines were later removed. Meaning, almost 13 million lines had to be written over 25 years for ~3.6 million lines to exist today. On average, each line of CPython had to be rewritten 12.9 / 3.6 or 3.5 times during its evolution.

![git log --numstat 7f777ed95 f3759d21dd --pretty='' | awk '/^[0-9]+[[:space:]]+[0-9]+[[:space:]]/ {added += $1;deleted += $2}END {print "Added:", added; print "Deleted:", deleted}' Added: 12,915,596 Deleted: 9,235,977](/articles/advent-of-code-golf-2025-2/countadds.png)

Rewrites in Code Golf

I experienced this purification via rewriting during Code Golfing, too. Every time I rewrote a part of my solution, the idea behind the algorithm crystallized more clearly - which in turn enabled me to shorten the code even more once again. Code Golfing now seems to me to be an interesting tool that may purify my algorithms down to their most necessary bits (I just need to remember to ungolf the code before putting it in production).

Interestingly, sometimes I would benefit from just physically fitting more of the algorithm lines on one screen. Reviewing a larger chunk of the algorithm at once, I often would realize a new rework I hadn’t thought of before, when the individual code lines spanned 3 screens. This uncannily resembles how an AI agent can reason only about the data fitting in its context window “screen”.

Wrap-up

That concludes my Advent of Code Golf for Christmas, but what about golfing for the New Year? Want about an interactive sand simulator with physics and video post-processing, rendering up to 400,000 particles at 60 FPS in less than 1024 symbols?

Or maybe an animated 3D-renderer with raytracing that fits in 1.5 Kb? (see post about the original un-golfed raytracer here)

Stay tuned.

P.S. Day 12

On day 12, you need to solve a packing problem.

Spoilers ahead

There is a spectrum of complexity in solving packing problems. From very easy “yes” or “no” answer on the ends of the spectrum (think: “no”, you can’t pack a train in a pocket no matter how hard you try; “yes”, you can always put a penny in a train carriage, no matter how tiny the carriage is) to extremely hard packing problems in the middle, where one may need to optimize every single bit of space to get a “yes” using latest research advancements.

But Eric is a nice guy. He never gives hard problems on the last day of Advent. And this time, there is a trick too. In the input data for day 12, there will ONLY be cases of “simple yes” or “simple no” problems. You don’t need to think about hard problems. Nice!

But. I promised myself in part 1 to NOT look ahead into the data and use this knowledge to inform my code. So what do I do?

I turned to lazy evaluation as my helper. Here is my solution to count the number O of solvable packing problems in the input, ungolfed, in general terms:

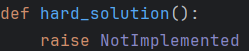

But how do I fit years of research into 300 characters I used for day 12? Well, I don’t:

This works, because else is never reached on our data. This still violates my promise not to look-ahead, indeed. But, I allowed it for day 12 because this was an intended solution, as long as I called the hard_solution() function in the last branch explicitly.5

I wish there were a popular leaderboard for Code Golfing, especially around AoC. I found and tried one leaderboard, and for Day 3, I even held the 1st place using python (2nd place across all languages) by the end of Christmas. But the platform wasn’t very popular, and it even didn’t allow submissions for some of the puzzles due to its limitations. It would have been more fun to compete with other people. Maybe I’ll make a leaderboard next year. ↩︎

For example,

my_list+=item,(note the comma) can replacemy_list.append(item), saving 6 characters. ↩︎Later, I also did the same to the “\n” (newline character) that I used in

str_variable.split("\n")eight times. ↩︎There is a genius tool pythongolfer that converts your code bytes into Unicode, and shortens the solution of x characters to x/2+25 characters. Applied to my code, it would have given me a result of 1417 characters (118.08 characters / puzzle). I didn’t use it because I didn’t find using it fun. ↩︎

In the Code Golf terms, it looks like a

o+=U(k)<=(x//d)*(y//d)or x*y>=U(A(k)*p)and h(), whereh()is thehard_solution()call. ↩︎